The Afterlife of the Sublime

In “The Afterlife of the Sublime” I explore a new history of aesthetic theory in the long eighteenth century. Previous histories of the sublime either describe a set of discontinuous historical practices that changed from author to author, or a single theoretical sublime that various authors were closer to or farther away from. Rather than tracing the concept of the sublime as a purely mental or theoretical construct, I instead use the new methods of quantitative analysis to trace the language that defines it throughout its appearances in theoretical, critical and literary writing in the two centuries between 1660 and 1860. The combination of critical and digital methods that characterize this project allow me, for the first time, to explore discontinuities and similarities in the work of the sublime as it is re-purposed throughout the eighteenth century. This project seeks to answer three questions: First, how and why did the sublime rise to critical prominence in the early eighteenth century? Secondly, why did it suddenly decline in usage at the end of the Romantic period? And finally, how does the work of the sublime continue even after the word itself disappears from aesthetic discourse?

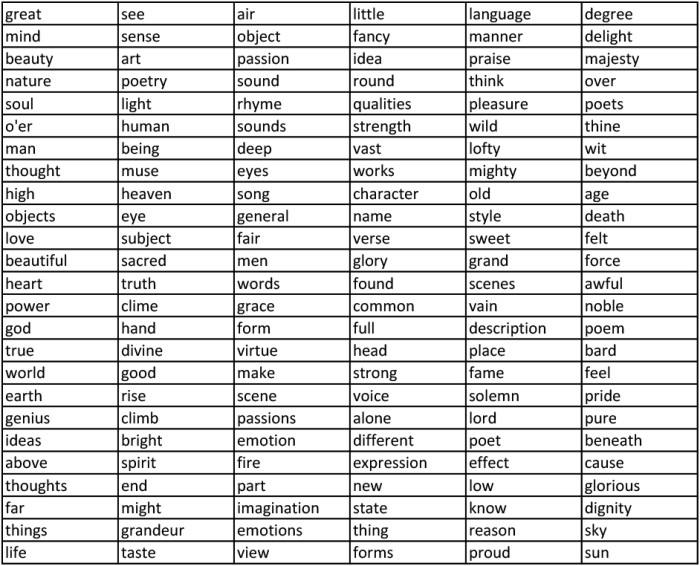

To answer these questions, the first phase of this project sought to identify the particular pattern of language that was distinctive of the sublime throughout the long eighteenth century. Working with a corpus of over 11,000 texts (primarily held by the Chadwyck-Healey and Eighteenth-Century Collections Online archives), I used a collocation analysis to identify the words that appeared distinctively within the 20 words before or after every appearance of the term “sublime” in the corpus. I chose 20 words as that was the average sentence length in my sample, ensuring that I was at least identifying words within one complete syntactic unit. This left me with 150 words that form the “language” of the sublime.

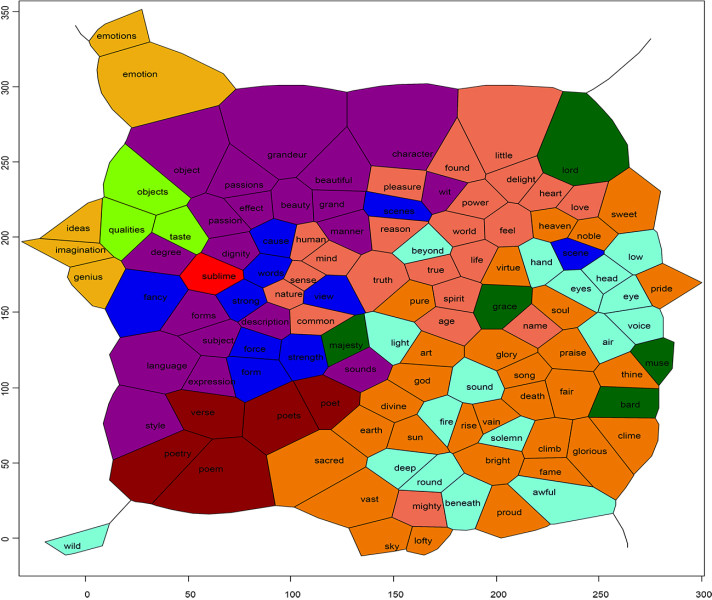

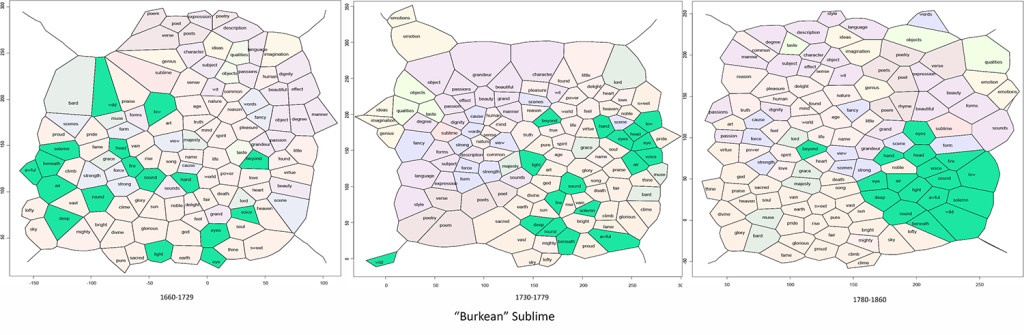

In its second phase, this project takes account of the fact that the language of the sublime does not form a single and stable pattern across the two centuries of my analysis: the sublime evolves. To trace the shifting patterns in this language, I created topographical maps of the relationships between these terms at each third of the historical period that I examine, deriving snapshots of the sublime at regular intervals throughout its history. Each Voronoi diagram below represents one period of analysis and each tile is a word that is distinctive of the sublime across the full 200 years that I examine.

The position of each tile is a function of its similarity of usage to the other terms within the vicinity of the sublime at that period. Two words that are close to each other appear together in similar frequencies within 20 words before or after the sublime during that 67 year period. Words that are farther away from each other are less likely to appear together in the vicinity of the sublime. The colors refer to the clusters of words from the corpus overall (identified through a series of hierarchical clusterings). By comparing the overall groupings of the words at a specific period to their similarities overall, we can see how individual discourses of the sublime form and dissolve over the two centuries of its prominence.

For example, the light blue tiles (highlighted in the imaged above) identify a set of terms that have to do with the physiological experience of the sublime, strongly related to that which Edmund Burke describes in his Philosophical Inquiry. In the first two periods, these words are scattered across the map: most are rarely used together. In the third topology, however, these terms suddenly cluster in a tight formation, revealing the emergence (and popularity) of Burke’s specific language of the sublime as an identifiable discourse. It is interesting to note that this happens two decades after the publication of Burke’s text.

Though these topologies, I am able to explore how each subset of terms creates patterns within the overall history of the sublime, which help to explain the historical changes to the discourse. Moreover, I can take the language of the sublime that I have identified and trace it into individual texts, revealing the patterns of the presence and absence of this language in the text itself.

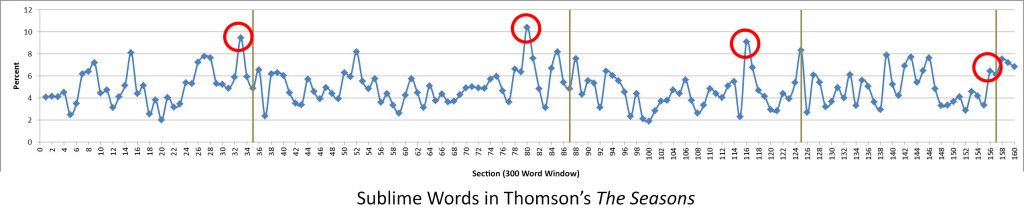

For example, in the above graph of James Thomson’s poem The Seasons, each point indicates the percentage of words that come from the language of the sublime within the average of a 300 word moving window in the poem. High points indicate strong concentrations of the language of the sublime. In Thomson’s poem, there is a distinct pattern: each section (identified by the vertical lines) begins with a relatively moderate peak, then a drop-off, followed by a high peak at the end of the poem. In the project, I describe how this reveals a strategy by Thomson to guide his readers through a “correct” experience of the poem using the language of the sublime. Following this critical method, I am able, through this project to reveal a new history of the sublime, and the aesthetics that it created, both in the patterns of language across its history, and within individual texts.